“Justice for All” is the title of a recently published report on access to justice that officially launched in Canada on May 30, 2019 at the Global Center for Pluralism in Ottawa.[1] The report was published by the Task Force on Justice. The Task Force is an initiative of the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies, a group of member states working towards a shared vision of how United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16.0—Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development; provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels—can be delivered. The Pathfinders have placed access to justice at the core of the effort to implement SDG 16. Their work further serves to highlight access to justice elements of the other 16 UN Sustainable Development Goals.[2]

The Justice for All Report Canadian launch event featured prominent global leaders, who each spoke to key findings in the report and the urgency of addressing the worldwide access to justice problem. The main speakers at the event were Mary Robinson, former Prime Minister of Ireland and Chair of the Elders,[3] Nathalie Drouin, Deputy Minister of Justice in the Government of Canada and Allyson Maynard-Gibson former Minister of Justice and Attorney General of the Bahamas. The International Development Research Centre, The World Bank, The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, The United Nations Development Program and the Open Society Justice Initiative are among the 26 international partners in the initiative. The Canadian launch was sponsored jointly by the International Development Research Centre, a branch of Foreign Affairs Canada and the Task Force on Justice.

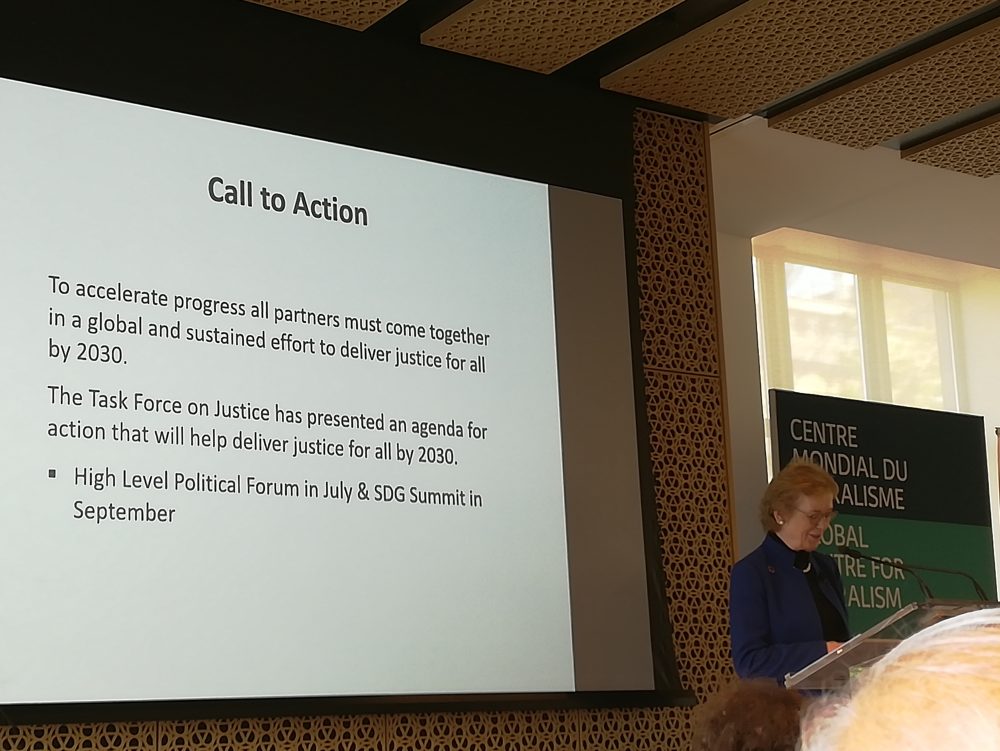

The Justice for All initiative is one of bold intent. At the heart of the Justice for All vision is the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a roadmap endorsed by the UN’s more than 190 member countries in 2015 to help create a “just, equitable, tolerant and socially inclusive world”. Justice is a thread that runs through all 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, it should be noted that the 2030 Agenda represents the first time that the United Nations has included a target that directly addresses access to justice in its global plan for action. Specifically, SDG 16.3 calls for equal justice for all by the year 2030.

The agenda for action of the Task Force is built around several overarching themes:

– Resolving the justice problems that matter most to people

– Preventing justice problems

– Creating opportunities for people to fully participate in their societies and economies; and

– Investing in justice institutions that work for people and that respond to their needs for justice.

Supporting national implementation of justice initiatives, increasing justice leadership, measuring progress, intensifying cooperation and building the global movement are also important parts of the agenda.

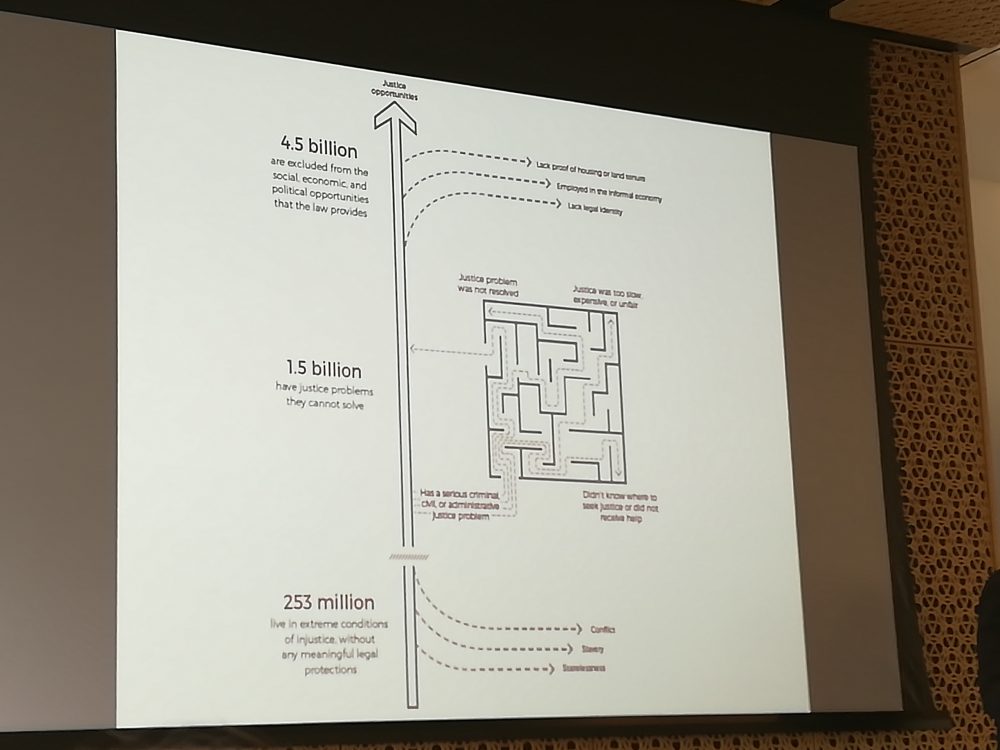

True to their name, the Task Force is a catalyst for concerted action. Though they are less involved in on-the-ground justice initiatives, they are helping to promote action on access to justice by advancing a global movement that is helping to raise awareness of the seriousness of the global crisis in access to justice, and bringing the importance of improving access to justice worldwide to the forefront of public consciousness and discourse. Doubtless, particular needs and solutions will exist in different parts of the world. In one jurisdiction legal identity documents and land titles may be fundamental problems blocking social development; in another, cost or timely access due to crowded dockets may be the main barriers limiting access to civil courts. The Task Force’s efforts recognize the complexity and diversity of the access to justice problem. In Canada, where provincial/territorial, national and international endeavors continue to work to move the dial on improving access to justice, the added attention that the Task Force’s “Justice for All” report launch in Canada has brought is welcomed.

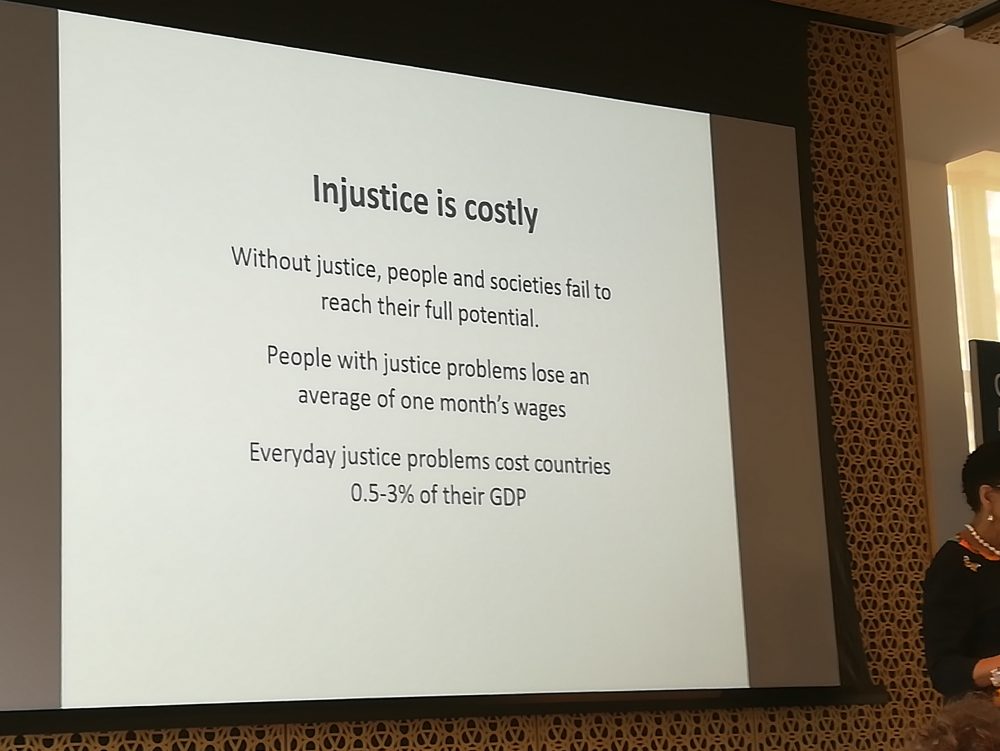

The cost of injustice is one of the main areas of concentration in the work of the Task Force. As pertains to this topic, the work of the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice (CFCJ) features prominently in the Task Force report. The CFCJ’s contributions include data from the national survey of Everyday Legal Problems and the Cost of Justice (2016) and a specially commissioned report on Costing the Justice Gap: Return on Investment for Justice Services by Civil Society Organizations (forthcoming 2019).

The work of the Task Force on Justice and the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies as well as other international organizations over the past few years since the United Nations issued its 2030 Agenda is encouraging. These efforts have applied the empirical research from the body of legal problems research conducted over the past 25 years and the policy implications that have flowed from this collection of socio-legal restudies to inform further research as well as to help, reenergize the access to justice movement. This includes building on early work from Canadians like Ab Currie and others to help push a recognition of the importance of public-centered efforts and the recognition of everyday legal problems as a central area of focus for legal institutions and legal reforms. The CFCJ’s ongoing efforts and support for the Task Force, the Pathfinder’s, the work of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other initiatives, as well as the Canadian Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family Matters (also featured in the “Justice for All” report) continue to be directed toward important, public-first, meaningful, justice-for-all goals and research efforts. Readers are encouraged to read Justice for All: The Report of the Task Force on Justice, April 2019 accessible at https://www.justice.sdg16.plus/report.

[1] The Justice for All report was published on April 29, 2019. See Task Force on Justice, Press Release, “Justice Systems Fail to Help 1.5 Billion People Resolve Their Justice Problems, New Global Report Finds” (29 April 2019) online: Pathfinders for Peaceful, Justice and Inclusive Societies <https://www.justice.sdg16.plus/report>.

[2] For the complete list of UN Sustainable Development Goals, see “United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform”, online: United Nations <https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs>.

[3] The Elders is an international, non-governmental organization of prominent public figures brought together by Nelson Mandela in 2007. For more information about The Elders, see “Who we are” online: The Elders <https://www.theelders.org>.