The Codify Project: Building a Free Database of Global Legislation

John WuWednesday, July 3, 2019

My name is John Wu. I’m a JD / MBA student between Osgoode Hall and Schulich School of Business. With my team, I’m currently building a free database of global legislation.

Why are you doing this?

I’m going to start off with a premise I hope most of you can get behind: legal information is difficult to access, and prohibitively expensive.

Anyone who has dealt with companies like Thomson Reuters or LexisNexis can attest to the steep costs of accessing their resources (for those who are unfamiliar, a pricing chart can be found here). While free resources are available through the good work of various legal information institutes, these alternatives are often seen as a poor man’s substitute to be used by small firms, non-profits, and organizations that cannot afford pricey subscriptions.

Over the course of the past year, I spoke to dozens of organizations being squeezed into this position, from human rights advocacy groups to resource providers for legal aid clinics. I heard the same story from almost everyone: lower budgets, and higher costs, leading to less resources being available.

This is problematic. Legal information should, in theory, be far more accessible than it currently is. The rule of law is premised on the idea that everyday citizens can access legal information, and subsequently understand the law. Despite this, the most useful legal resources are consistently being locked behind paywalls, under a business model that tries to extract as much value from each individual customer.

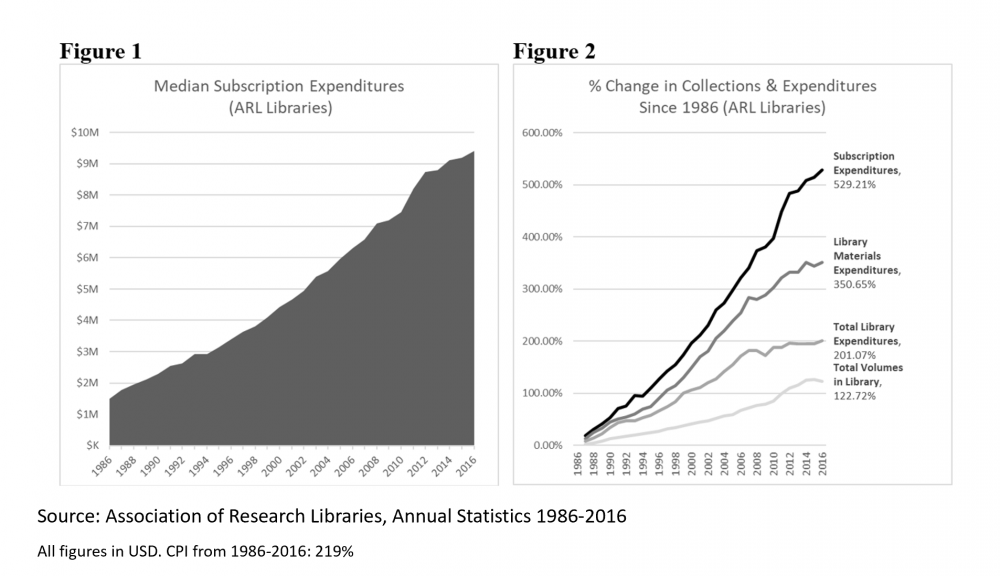

And these paywalls are getting higher. Based on 20 years of data from the Association of Research Libraries, subscription prices from major publishers have been, and are continuing to increase at an astounding rate. As a result, libraries across the country are cutting down on the resources they provide in an ongoing effort to manage costs.

The rising cost of legal information goes against the general trends we’ve been observing almost everywhere else. After all, thanks to advances in technology, information collection and communication are easier than ever. This has transformed a once scarce resource into a sea of abundance, allowing for the creation of websites like YouTube and Wikipedia, which have revolutionized access to information across the globe.

Believing this same sort of transformation can happen with the law, we started the Codify Project. By creating a free database of global legislation, we hope to enable researchers to make more discoveries, assist lawmakers in drafting better laws, help legal professionals deliver better advice, and empower the everyday citizen to connect with the laws around them.

Wouldn’t that take decades of work?

While it may seem like a Herculean task for a team of two full-time employees, we have a secret weapon. The Codify System is an array of software which automatically scrapes, formats, and stores legal information.

Once the information is stored, it is automatically updated by the Codify System whenever there is a change, whether it’s an amendment to a pre-existing law, or a new law being introduced. The database is therefore always up to date and grows even without human intervention.

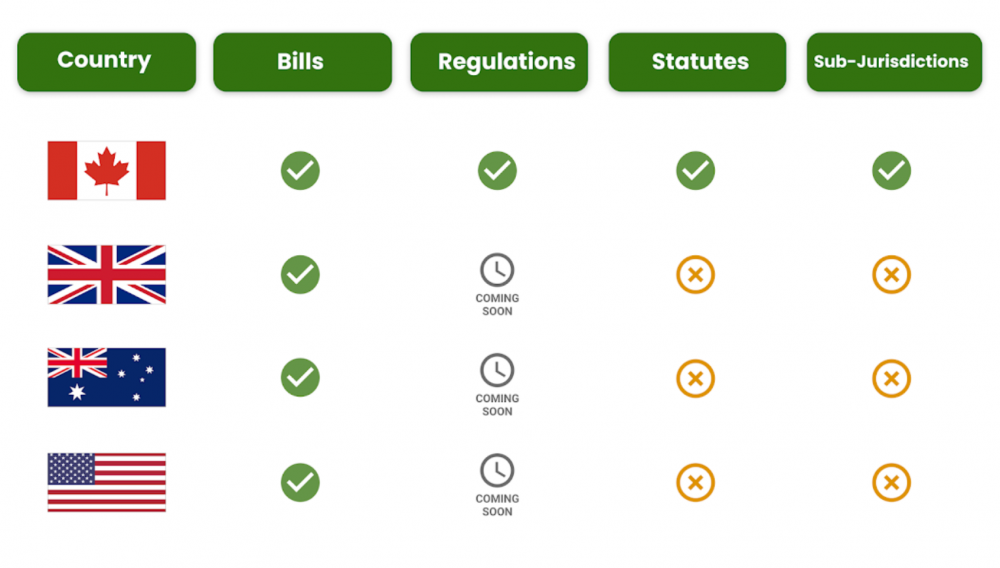

Using the Codify System, which we developed with the support of Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, we have built up the largest free database of Canadian legislation, containing all bills, regulations, and statutes, from every province and territory.

Because we’re using an automation, we can make improvements to our system with each jurisdiction we complete, allowing our program to complete the next jurisdiction faster. Based on our current data ingestion schedule, we should have the complete data set for 4 countries completed by the end of 2019.

An additional benefit of using technology to do the work is that it drives our marginal cost down, far lower than if we were doing this manually. This is what allows us to make our database free for the public.

Why legislation?

We decided to focus on legislation for two reasons.

The first is the inaccessibility of legislation, despite it being “free” in theory. While there are a number of reasons why this is, including the use of dense legalese and the increasing use of omnibus bills, the heart of the issue lies in how fragmented legislation is.

Statutes, bills, and regulations are all published through different sources (Justice websites, legislative assemblies, and gazettes respectively). Thus, to piece together the puzzle, one must learn how to navigate and gather information from numerous online resources, many of which are painfully out of date.

By codifying all this information into a single, freely-accessible database, we are making the legislative schema more accessible not just for humans, who can now access all information types on a single website, but for machines as well.

The second part is very important. Machines have a very difficult time when it comes to gathering information from web pages. The distinction between content and code can be blurry, and semantic meaning is often lost when extracting text. With legislation, this problem is compounded due to the patchwork of publication standards and data types. This makes it very difficult to apply technologies such as language processors.

By extracting information from government websites and documents, and standardizing it into a machine-readable language, the Codify System makes the database that much more useful for the development of computer applications, allowing complex programs to be built with relatively little effort.

One example of what is possible is Codify Updates, a website we built to help legal professionals stay aware of changes to the law.

Twice a day, Codify Updates publishes every legislative change in Canada. With a free account, users can create customized feeds to track the laws that matter to them, set up live email alerts, and use the built-in search engine to discover new insights.

A few years ago, the idea of software automatically tracking every legislative change seemed implausible. With a machine-readable database, this is but one relatively simple example of what is possible.

You mentioned two reasons. What’s the second?

In addition to its inaccessibility, legislation was also interesting to us because it impacts such an enormous range of stakeholders. Beyond lawyers and researchers, it is vital to the work of politicians and administrators, HR representatives and compliance teams, lobbyists and grassroots activists and more.

With such a diverse and interesting group of communities, which have largely been cloistered up until now, we see a lot of potential in building an open platform where they can engage and interact with the data.

After all, there are countless use cases for a database of international legislation. Some examples we’ve thought of include: (1) a political website for keeping tabs on which bills a politician sponsored, (2) a compliance tool for federally regulated financial institutions, (3) a comparative law search engine, (4) the translation of English laws into braille and American sign language.

These are all fantastic use cases which are well within the realm of possibility, which we are unable to explore due to time and resource constraints. By engaging with these stakeholder groups and providing them with the data, we hope to enable them to execute on the use cases that matter to them, and further increase the reach of our database.

What is the endgame?

In 1984, the very first Hackers Conference was held in Marin County, California. Though a relatively obscure event at the time, this gathering of designers, programmers, and engineers planted the seed of modern cyberculture, bringing together numerous titans of industry, including Apple co-founder, Steve Wozniak, and the father of hypertext, Ted Nelson.

It was at this conference that the organizer, author Stewart Brand, uttered his now famous words: “Information wants to be free.”

Those present immediately seized upon this quote, transforming it into a battle cry for the relentless march of the internet. In the ensuing decades, the importance of this statement has only swelled, with some calling it “the single dominant ethic in [the digital] community”; and the “defining slogan of the information age.”

As catchy as the expression is, the actual quote, made during a discussion on intellectual property between Brand and Wozniak, was much more nuanced.

“On the one hand information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against each other.”

Looking at the current state of the legal information market, it is worth reflecting on how this paradox has played out. On the one hand, there is more legal information available than ever before. Podcasts, blogs, and online legal guides have enabled countless legal professionals to share their knowledge with diverse audiences of lawyers and non-lawyers alike. And the digitization of laws has made it so that anyone can, at least in theory, see the laws of the land, without having to visit a courthouse library.

On the other hand, getting access to legal information, in the right time and place, has become more expensive than ever. Professionals are expected to get better information, and get it faster, to the point where judges feel comfortable penalizing lawyers for failing to use more sophisticated research tools. While a push to improve efficiency is not itself a bad thing, coupled with the high cost of legal information, this only creates further divisions between the haves and the have-nots, while strengthening the oligopoly of the big publishers.

We don’t expect this tension to disappear. But we hope the Codify Project will help shift the current dynamic. We believe it is the right of every citizen to have free and easy access to their laws. And through the power of technology and innovation, we have the means to provide it.

Where can I learn more?

If you would like to learn more, you can access our website here.

We are currently in the process of putting together a committee of industry leaders, to act as a preliminary board for the project. If you are interested in joining this committee, and want to learn more about its responsibilities and current membership, please email the author at john.wu@codifylegalpublishing.com.

John Wu, JD / MBA (Candidate), is the Director of Codify. As a law student in 2017, he was recognized by the Attorney General of Ontario as a rising star in legal-tech, and was given an award for his work in access to justice. Since then, he has founded an after-school program that brings legal education to local youth, as well as delivered presentations before the Ontario Bar Association Tech Expo and the Canadian Association of Law Librarians. Prior to entering law school, John worked as a researcher in the Department of Ophthalmology at St. Joseph’s Hospital. In his spare time, he enjoys watching science fiction and playing the guitar.