How lawyers resolve family law disputes

J.P. BoydTuesday, November 4, 2014

This past July I was able to sample the views of 167 lawyers and judges attending the Federation of Law Societies of Canada‘s National Family Law Program in Whistler, British Columbia through a survey designed and implemented by two prominent academics and the Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family. The survey asked questions about participants’ views on shared parenting and shared custody, litigants without counsel, and dispute resolution.

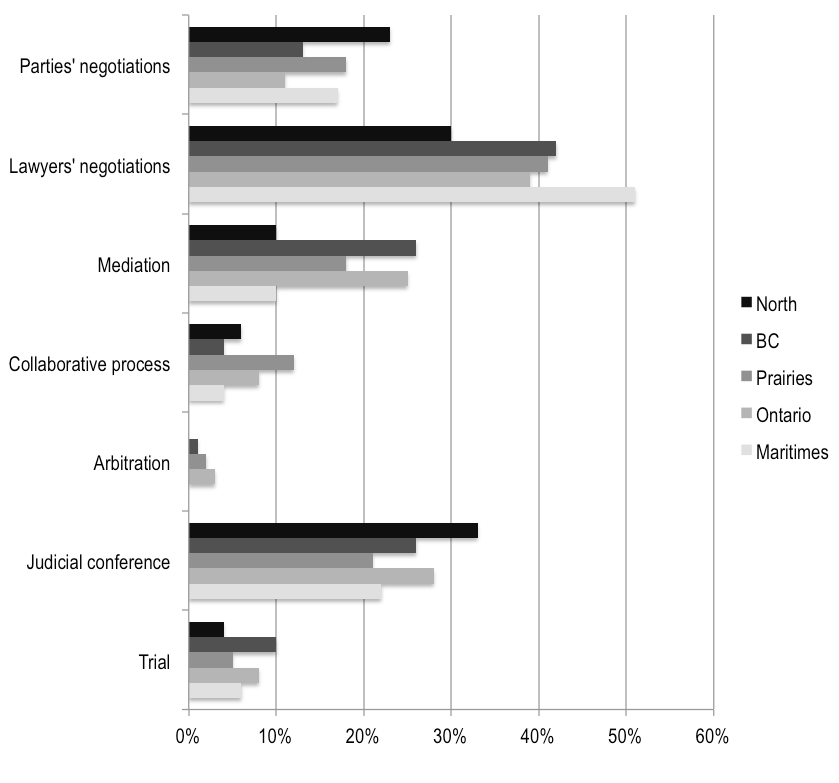

In the course of digesting the resulting data for a report, I noticed something very interesting about the information we’d collected on dispute resolution. We had asked lawyers to tell us the percentage of their family law cases which are ultimately resolved by: arrangements made by the parties themselves; negotiation involving lawyers; mediation; collaborative settlement processes; arbitration; through court with the assistance of a judge at an interim hearing or a judicial conference; or, through court at trial. Here’s what the numbers told us:

As you can see, the lion’s share of cases are resolved through negotiation, primarily negotiation involving lawyers. (If you click on the image, you’ll get a larger, clearer version of this chart.) By region, lawyers reported that their family law cases were settled through lawyer-involved negotiation as follows:

- North (Northwest Territories, Yukon): 23.3%

- British Columbia: 41.1%

- Prairies (Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan): 37.4%

- Ontario: 38.7%

- Maritimes (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia): 50.6%

The rate of resolution by negotiation in the maritimes is astonishing at more than half of lawyers’ files. British Columbia sits in second place with two out of five files resolved through negotiation, followed closely by Ontario.

Mediation is popular in British Columbia and Ontario, but less so in the north, the prairies and the maritimes, perhaps because of smaller populations or a smaller number of trained mediators:

- North: 10.0%

- British Columbia: 25.5%

- Prairies: 17.9%

- Ontario: 24.8%

- Maritimes: 10.0%

I was surprised to see relatively low rates of resolution through collaborative settlement processes, as it seemed to me that collaborative processes are more widely used in British Columbia and Alberta, but I wasn’t terribly surprised to see the low rate of resolution through arbitration. Arbitration has been widely accepted by the Ontario family law bar, and is becoming more accepted in British Columbia as a result of it’s new family law legislation; in other provinces arbitration isn’t used at all.

The relatively high rate of settlement through pretrial court processes, however, reflects my own experience as a family law lawyer. Quite often litigation is commenced not because a trial is anticipated but in order to deal with urgent problems, compel document disclosure, signal a party’s sincerity and commitment to a particular position, or move settlement discussions along. Judicial settlement processes, such as Judicial Case Conferences and Settlement Conferences in British Columbia or Judicial Dispute Resolution hearings in Alberta, are extraordinarily effective ways of getting past the stumbling blocks to settlement. Quite often the judge’s considered opinion of the likely outcome or of the merit of a party’s case is enough to modify unreasonable positions and encourage settlement.

By region, lawyers reported that their family law cases were settled by pretrial court processes involving a judge as follows:

- North: 33.0%

- British Columbia: 25.8%

- Prairies: 21.1%

- Ontario: 28.2%

- Maritimes: 21.6%

Finally, the rates of resolution by trial, which I, and I believe most lawyers, view as an option of last resort, were wonderfully low. The rate of resolution by trial was higher than resolution by arbitration but about the same as resolution through collaborative processes, and only a fraction of the rates of resolution by lawyer-involved negotiation and pretrial conferences. By region, lawyers reported that their family law cases were settled at trial as follows:

- North: 4.4%

- British Columbia: 10.0%

- Prairies: 5.4%

- Ontario: 7.6%

- Maritimes: 5.9%

Here British Columbia is a surprising outlier with a rate of resolution by trial significantly higher than everywhere else except perhaps Ontario, which had the next highest rate of resolution by trial. However, bearing in mind that the people who need to hire a lawyer to deal with their family law dispute generally have fairly complex and sometimes intractable problems, an overall rate of resolution by trial of 10.0% and 7.6% isn’t bad. Breaking things out by province, however, Alberta had the lowest rate of resolution by trial at 3.8% (what an incredibly low number; that’s less than 1 in 25 of lawyers’ family law files!) and Saskatchewan the highest at 12.9%.

These numbers are very reassuring. They suggest that family law lawyers emphasize dispute resolution processes other than trial in their practices, and tend to resolve their files primarily through lawyer-involved negotiation, judicial conferences and mediation. The relatively low rates of resolution through collaborative processes are explained, I think, by the facts that collaborative practice is well established in some provinces but is still developing in others and that not all family law disputes are amenable to this sort of intensive, dialogue-based process. The low rates of resolution through arbitration are explained by the different legislative treatment of non-commercial arbitration across Canada and the legal cultures that have developed as a result. In Ontario, arbitration is widely accepted and entrenched in family justice; in British Columbia, however, arbitration has just moved onto the scene as a result of its new family law legislation.

From an access to justice perspective, these numbers suggest that people are better able to afford counsel to manage their cases from start to finish as so few cases wind up being resolved through costly trials. However, you have to be able to afford counsel to begin with to enjoy the luxury of resolution other than by trial, and, as we know from research previously published by the Institute, settlement short of trial is significantly less likely in cases where one or more parties are without counsel than if all parties are represented by counsel.

At the end of the day, these data reflect very well on lawyers’ approach to their clients’ cases. However, clients must still be able to afford the services of counsel or they will, more likely than not, face the trial counsel would have helped them avoid.

A note about the data

The greatest number of responses to this question were received from Alberta (about 28 on average), British Columbia (about 38) and Ontario (about 13); all other provinces and territories yielded 10 or fewer responses. As a result, I have lumped the data together by region in an effort to produce more meaningful numbers, giving responses as follows:

- North: range of 5 to 6 respondents

- British Columbia: range of 5 to 41

- Prairies: range of 35 to 44

- Ontario: range of 11 to 15

- Maritimes: range of 13 to 16

The survey received no responses from judges and lawyers practicing in Nunavut or Prince Edward Island. A small number of responses were received from Quebec practitioners; I have excluded these responses on the ground that Quebec’s civil law system is not readily comparable with the common law system used throughout the rest of Canada.

This piece originally appeared on Access to Justice in Canada.