Legal secondary consultation (LSC) is an innovative and promising legal aid delivery model in which a legal service professional provides one-on-one advice to a service provider in a social services agency or a community organization. This assists the provider to resolve problems for clients seeking help. The final report by CFCJ senior research fellow, Dr. Ab Currie on a legal secondary consultation pilot project with three community legal clinics in Southwest Ontario is now available on the CFCJ website. Read “Legal Secondary Consultation: How Legal Aid Can Support Communities and Expand Access to Justice” here.

Access to Justice: Current Crop of Law Students Committed, Enthusiastic

This article originally appeared on The Lawyer’s Daily on April 18, 2018. It is the seventh article in The Honourable Thomas Cromwell’s exclusive Lawyer’s Daily column dedicated to access to civil and family justice.

It is easy to get discouraged by the slow pace of progress on improving access to justice. But a constant source of encouragement is the enthusiasm and commitment of the current generation of law students.

Everywhere I encounter today’s law student, I see concern about the injustice of our current poor level of access to justice, interest in what can be done to improve it, and commitment to be part of the change to bring about that improvement. The interest and enthusiasm of students for work in legal clinics and with Pro Bono Students Canada and other access-oriented activities are some of the tangible evidence of their concern, interest and commitment.

I recently had the privilege and pleasure of being part of another manifestation of law students’ engagement with access to justice. The Society of Law Students at Thompson Rivers University organized a two-day conference on access to justice. The program can be found here.

In addition to presentations by students and faculty, the students hosted a number of special guests, including the Honourable Robert Bauman, chief justice of British Columbia, the Honourable Len Marchand, a justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia and the Honourable David Eby, minister of justice and attorney general of British Columbia. The organization was entirely student-directed and participation throughout the student body was significant.

I spoke with one of the co-chairs of the conference, Dave Barroqueiro, who is a second-year student. Dave’s take on access to justice and the profession’s role in improving it is bang on and shows how the next generation of lawyers understands the problem and wants to help to solve it. I asked him what lessons he drew from his work on the access to justice problem.

He started by speaking of the need for culture change: “The culture of law and of lawyers must change, and society isn’t willing to wait any longer. The legal industry itself, the profession’s self-insulation, and our paralyzing risk aversion, are undoubtedly major contributors to the access to justice crisis in Canada.”

He also recognized the role that lawyers and legal profession should and must play in improving access to justice: “ … the key to unlocking the solution to the access to justice crisis rests in the hands of legal professionals themselves — we simply need to be willing to adjust to the rapidly changing needs and demands of contemporary, digital-age clients.”

He stressed what he believes is the important part technology can have in bringing about the necessary changes: “Increasing the agility of lawyers and the efficiency of the delivery of legal services ought to be the principal focuses of the legal profession going forward.”

Finally, he recognized what many commentators have stressed: The necessity of responding better to the needs of the public seeking legal services. As he put it, “To think that we, even as a self-regulating profession, can overwhelm consumer-driven market forces for much longer is a delusion. The future practice of law will depend on an active, informed understanding of client needs.”

My impression is that Barroqueiro’s views are not unique. I believe they are shared by a lot of law students. Those in positions of power and influence should encourage and support this kind of thinking in the next generation of lawyers and at least make a start on the important work that they are keen to take up as they progress in their legal careers.

We are leaving them a big access to justice challenge. But I believe that they are up to it.

The Honourable Thomas Cromwell served 19 years as an appellate judge and chairs the Chief Justice’s Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family Matters. He retired from the Supreme Court of Canada in September of 2016 and is now senior counsel to the national litigation practice at Borden Ladner Gervais.

Access to Civil Justice in Canada Has Been In a Steady State, But a Bit Low

Since 2009 the World Justice Project (WJP) has gathered data measuring the rule of law in countries around the world. One of the eight components of the WJP Rule of Law Index is Access to Civil Justice.[1] Canada’s overall score on the access to civil justice dimension was 0.72 in the 2016 Rule of Law index.[2] This put Canada in 19th place globally and 12th among 24 countries in the same region. In terms of overall Rule of Law scores, Canada ranked 12th among 113 countries.

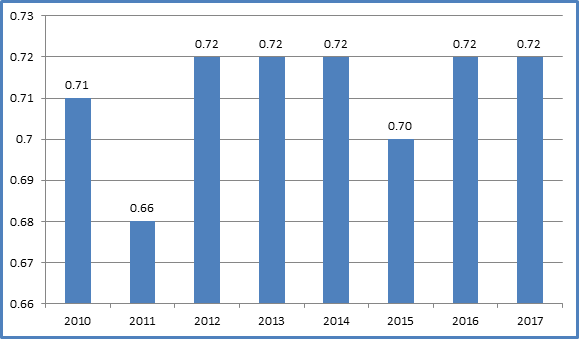

Globally, the Netherlands, Germany and Norway received the highest scores for access to civil justice at 0.88, 0.86 and 0.85 respectively. The United Kingdom ranked 16thwith a score of 0.75 and the United States ranked 28th with an access to civil justice score of 0.65. Figure 1 shows Canada’s overall score for access to civil justice from 2010 to 2017.[3]

The recently published 2017 WJP Rule of Law Index reveals a similar trend. For the 2017 Index, Canada’s overall score on the access to civil justice dimension was 0.72 which placed Canada 20th among 113 countries. Regionally, Canada once again ranked 12th among 24 countries. The top ranked countries for access to civil justice were the Netherlands with a score of 0.87, Denmark with a score of 0.86 and Germany with a score of 0.85. For the access to civil justice Rule of Law measure, the United Kingdom’s global rank for 2017 was 14 out of 113 countries with a score of 0.75 and the United States ranked 26th, with a score of 0.67.

Figure 1: Access to Civil Justice Scores for Canada, World Justice Project, 2010 to 2017

Access to civil justice in Canada has been in a steady state over the period measured by the WJP. The level of access to justice in Canada is not poor by global standards. However, according to the measures used in the WJP, scores on access to civil justice have been consistently lower than many other high income countries.

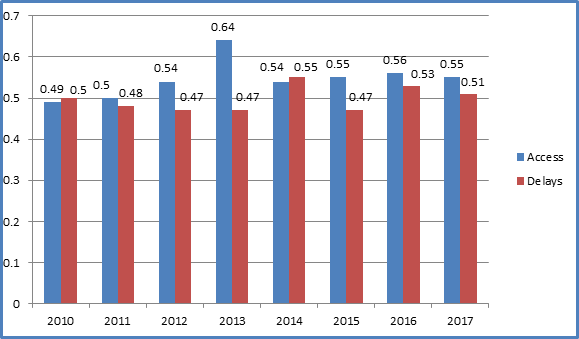

Among the six components of the access to civil justice index[4] the two that have been consistently low over the years have been accessibility and affordability and the absence of undue delays. Figure 2 shows Canada’s scores on these two components over the 2010 to 2017 time period.

Figure 2: Canada Scores for Accessibility and Absence of Unreasonable Delay, World Justice Project, 2010 to 2017

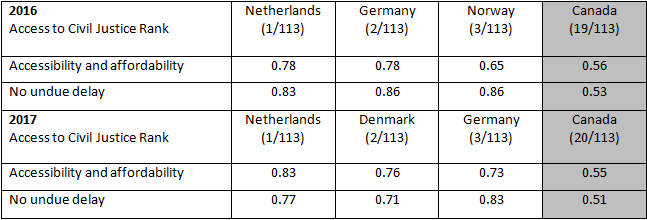

Compared with Canada’s overall access to justice score of 0.72 in the 2016 survey and 0.72 in 2017, the score for accessibility and affordability and for absence of undue delays were considerably lower, 0.56 and 0.53 respectively in 2016 and 0.55 and 0.51 respectively in 2017.

By way of comparison with Canada, the scores for accessibility and affordability and for undue delay over the past two years for the three countries ranked highest on access to civil justice are all higher than the Canadian indicators.

Table 1: Scores for Accessibility and Absence of Unreasonable Delay, World Justice Project, Five Countries, 2016 and 2017

Why is the level of access to civil justice in Canada consistently and markedly lower than these and other high income countries? Why is Canada apparently unable to break out of this pattern? Reducing something very complex and multifaceted such as access to justice to a set of numbers might be greeted with some discomfort among readers. Further, distilling the state of access to civil justice down to a single set of quantitative measures for a federal state with considerable variations of all sorts among the 13 Canadian jurisdictions may well increase the skepticism. However, there are always trade-offs. The comparable measurement and consistent data collection over a decade that has been achieved by the WJP has considerable value for comparative study among roughly similar high income countries.

Why do the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Norway and other countries consistently outperform Canada on scales of access to civil justice, in particular on measures of accessibility and affordability and fewer delays? The differences might be due in part to some of the inquisitorial elements in some civil justice systems, or by the more widespread use of legal expenses insurance, by greater accessibility of legal aid or, possibly, by differences in legal consciousness and legal capability among the public in some countries compared with Canada. Comparisons involving different systems of justice must always be approached with great care. Direct transfers of ideas and structures are rarely workable. However, we have an access to justice gap to fill. Knowing what works in other countries could provide useful knowledge about approaches worth considering and innovations that might be applicable with appropriate modifications in this country. As such, the WJP offers a valuable basis for comparative study and learnings on ways to improve access to justice.

[1] The eight dimensions of rule of law measured in the WJP Index are: constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice and criminal justice. https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/wjp-rule-law-index/wjp-rule-law-index-2016/factors-rule-law.

[2] The scale is from 0.0 to 1.0, with scores near 0.0 indicating low levels of A2J.

[3] Because of changes in the indicators after 2009 the measures are not compatible with data in the later surveys and are omitted from the graphs.

[4] The six indicators for civil justice with the Canada scores for 2016 indicated in brackets are: accessibility and affordability (0.56), absence of discrimination (0.65), absence of corruption (0.88), no improper government influence (0.89), no unnecessary delay (0.53), effective enforcement (0.73) and impartial, accessible and effective ADR’s (0.82).

New Research on the Suitability and Cost of Family Law Dispute Resolution Processes

There is perhaps no area of law where the emotional and far-reaching effects of disputes weigh as heavily on those experiencing them as family law. There is now wide-scale recognition from within the justice community[1] of the need for reforms in family law that reflect progressive values, which offer a continuum of adversarial and non-adversarial dispute resolution methods, and which contemplate modern and innovative service delivery processes. However, there remain significant gaps in the research available on the costs, overall satisfaction with, and benefits and limitations of the dispute resolution methods commonly available to address family law problems. Understanding what works, for whom, in what ways, and at what costs will help to shape policies that will serve the needs and interests of those who experience family law problems and whose lives are significantly impacted by the outcomes of family disputes.

The Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family (CRILF), in partnership with the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice (CFCJ), and with support from the Alberta Law Foundation and the CFCJ’s SSHRC-funded Cost of Justice research grant[2], recently conducted a study to measure the cost implications, effectiveness and suitability of four dispute resolution methods for family law disputes: litigation, collaborative processes, mediation and arbitration.

The primary objectives of this study were to:

- Aggregate cost data on the four dispute resolution methods evaluated;

- Gain insight on experiences with, and perceptions of processes to resolve different family problems;

- Apply a modified social return on investment (SROI) analysis that offers a common set of parameters around which to compare the financial impacts and social value of each method of dispute resolution relative to the seriousness of the family law problem; and

- Identify information that could prove useful for shaping programs, informing policies or services, and driving thinking about opportunities for reducing costs and improving overall experiences with dispute resolution in the family law context.

The study involved an online survey of lawyers practicing in family law in order to gather information about their use of, and views on collaborative processes, litigation, mediation and arbitration.[3] A total of 166 lawyers, practicing in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Nova Scotia completed the survey. The survey, which consisted primarily of closed-ended and rating scale questions, was organized by dispute resolution process, with similarly worded questions included in each section. Questions related to the cost of services were open-ended and respondents were also asked a series of demographic questions about age, gender, location and year of call to the Bar.

The survey resulted in a number of interesting findings and revealed high levels of consensus among lawyers as to their preferences for using certain methods of dispute resolution over others, based on various considerations including: the best interests of children, threats to safety, reducing potential for conflict. As for specific questions around cost, lawyers who participated in the survey offered a range of billing amounts for their professional services (including fees and other related services). For persons who experience family law problems, as well as for researchers, policy makers and other justice stakeholders, these cost estimates offer useful data points for better understanding and informing discussions around the costs, value, and benefits associated with using collaborative processes, arbitration, mediation and litigation to resolve family law problems.

In addition to a comparatively lower cost range for resolving disputes – from $1,000 to $100,000 — 94.0% of family lawyers agreed that the results that they achieve through collaborative processes are in the interests of the client and 98.9% agreed that the results are in the interests of the client’s children. Conversely, 36.1% agreed that collaborative processes are suited for high-conflict family law disputes. By contrast, 87.1% of lawyers disagreed that litigation was cost-effective, with the cost range for resolving disputes through litigation reported between $2,000 and $625,000. Another striking statistic in the use of litigation was the number of respondents — only 2.8% – who “strongly agreed” and a further 28.4% who “agreed” that the results achieved through litigation are in the client’s interest. Further, 30.2% agreed (strongly or otherwise) that the results are in the interest of the client’s children. However, with respect to processes best suited for high-conflict disputes, litigation was seen as a suitable process by 64.2% or respondents.

By way of comparison, the cost range indicated for resolving family problems through mediation was $630 to $250,000 and the cost range given for resolving family justice problems through arbitration was $2,500 to $100,000. It should be noted as well that the cost estimates presented here do not include the costs to engage other professional services (e.g. financial specialists, child specialists, etc.) as part of the dispute resolution process. Questions related to those costs were included in the survey and data on the hourly and total costs for those services are discussed in the final report. Also of note, 90.2% of respondents agreed that results achieved through mediation are in the client’s interest (and 85.4% agreed it is in the interest of the client’s children), while 34.2% agreed that the results achieved through arbitration are in the client’s interest (and 39.5% agreed that they are in the interest of the client’s children).

There is undeniably more work to be done to get a comprehensive view of the costs, benefits and appropriateness of various dispute resolution methods in addressing problems in family law. As debates ensue about changes to family law in Canada, and as we contemplate ways to improve access to justice, empirical data from studies like this will offer important insights into areas where support and resources can be directed to improve outcomes in family law.

The Evaluation of the Cost of Family Law Disputes: Measuring the Cost Implication of Various Dispute Resolution Methods report is available on the CFCJ website: https://www.cfcj-fcjc.org/sites/default/files/docs/Cost-Implication-of-Family-Law-Disputes.pdf.

[1] See, for example, the national Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family Matters, Roadmap to Change report (2013).

[2] The Cost of Justice project is a 7-year (2011-2018), Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) funded CFCJ research project that examines the social and economic costs of Canada’s justice system. Information on the Cost of Justice project is available on the CFCJ website here: https://cfcj-fcjc.org/cost-of-justice.

[3] For this project, the CRILF also developed a client survey that was intended to serve as a source of data about experiences with, and relative costs of, the four dispute resolution methods from the perspective of those experiencing family law problems. For practical reasons (discussed further in the final report) of confidentiality and client access, this information was not available.